There’s a question that comes up a lot in the mushroom community: “Why does a single trip sometimes change the way I feel for weeks or even months afterward?”

It’s a fair question. Psilocybin is out of your system within hours. The trip is over by bedtime. So why do the benefits — the lifted mood, the new perspective, the feeling that something fundamental has shifted — stick around so long after the compound is gone?

The answer, according to a growing body of neuroscience research, is that psilocybin doesn’t just change the way you think. It changes the physical structure of your brain.

We’re talking about real, measurable, microscopic growth — new connections between neurons that weren’t there before. And the most exciting part? These changes happen fast, and they last.

This blog breaks down the science in plain language. No PhD required. Just curiosity.

First, a Quick Brain Anatomy Lesson (We’ll Keep It Simple)

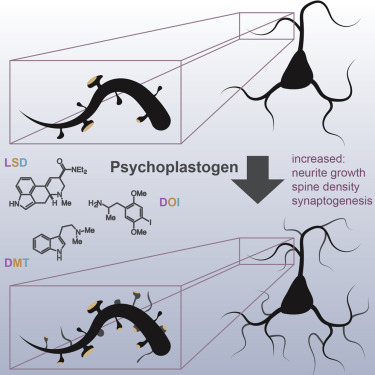

To understand what psilocybin does to your brain, you need to know about three things: neurons, dendrites, and dendritic spines.

Neurons are your brain cells. You have roughly 86 billion of them. They communicate with each other by sending electrical and chemical signals across tiny gaps called synapses.

Dendrites are the branch-like extensions that stick out from each neuron. Think of them like antennae — they receive incoming signals from other neurons.

Dendritic spines are tiny mushroom-shaped bumps that sit along those dendrites. Each spine is a connection point — a place where one neuron receives a signal from another. The more spines you have, and the bigger they are, the more connections your brain can make. More connections means better communication between brain regions, faster processing, and greater cognitive and emotional flexibility.

Here’s the critical part: depression, chronic stress, and anxiety physically shrink and destroy these dendritic spines. People with major depression have measurably fewer spines — especially in the prefrontal cortex, the region responsible for mood regulation, decision-making, and self-awareness. If you want to understand more about how psilocybin interacts with this part of the brain, our blog on How Shrooms Make You Feel is a great starting point.

Depression literally strips your brain of connections. And that’s where psilocybin comes in.

The Yale Study That Changed Everything (2021)

In July 2021, a research team at Yale University published a study in the journal Neuron that sent shockwaves through the neuroscience world. Led by Dr. Alex Kwan, an associate professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, the study provided the first direct evidence that a single dose of psilocybin physically grows new neural connections in a living mammalian brain.

Here’s what they did: using an advanced technique called chronic two-photon microscopy, Kwan’s team tracked 1,820 individual dendritic spines in the frontal cortex of living mice over multiple days. They gave one group a single dose of psilocybin and the other a saline placebo, then watched what happened.

The results were striking.

Within 24 hours of a single psilocybin dose, the mice showed approximately a 10% increase in both the number and size of dendritic spines in the medial frontal cortex — the mouse equivalent of the human prefrontal cortex.

But here’s the part that really made headlines: those new connections were still there a month later.

Dr. Kwan put it plainly: “We not only saw a 10% increase in the number of neuronal connections, but also they were on average about 10% larger, so the connections were stronger as well. It was a real surprise to see such enduring changes from just one dose of psilocybin.”

The study also found that psilocybin reversed stress-related behavioral deficits in the mice and boosted excitatory neurotransmission — meaning not only were the new connections growing, they were actively communicating.

This was huge. For the first time, researchers could literally see psilocybin building new brain architecture, one spine at a time.

Why This Matters for Depression

Remember those dendritic spines we talked about? Depression destroys them. The prefrontal cortex of a person with chronic depression looks physically different under a microscope — fewer spines, thinner dendrites, weaker connections.

Traditional antidepressants like SSRIs work by increasing the availability of serotonin in the brain. But they don’t directly rebuild lost connections. They manage symptoms, often for years, without addressing the underlying structural damage. And they can take 4–6 weeks to produce noticeable effects.

Psilocybin appears to work differently. Instead of just adjusting brain chemistry, it promotes the physical regrowth of the neural infrastructure that depression erodes. And it does it fast — within 24 hours.

This is why a single psilocybin experience can produce antidepressant effects that last weeks or months. It’s not just a chemical mood boost that wears off. The brain has physically rebuilt connections that support healthier patterns of thought and emotion. The hardware has been upgraded, not just the software.

Multiple clinical trials — from Johns Hopkins, Imperial College London, and NYU — have shown that one or two doses of psilocybin, combined with psychotherapy, can produce significant reductions in depression and anxiety that persist for 6 to 12 months. The Yale spine density research gives us a plausible biological explanation for why.

The 2025 Follow-Up: Psilocybin Rewires Entire Brain Networks

The Yale team didn’t stop there. In December 2025, Kwan’s lab (now at Cornell University) published a follow-up study in the journal Cell that went even deeper.

The original 2021 study showed that psilocybin grows new spines. But it left a key question unanswered: where do those new connections lead? Growing spines is great, but if they’re connecting to random neurons, that’s not necessarily therapeutic. The team needed to map which brain regions were being wired together.

To do this, they used an ingeniously modified rabies virus — engineered to jump from neuron to neuron without causing disease — as a biological GPS system to trace psilocybin’s rewiring across the entire mouse brain.

What they found was remarkable: psilocybin’s rewiring is network-specific. It doesn’t randomly grow connections everywhere. Instead, it selectively strengthens pathways from sensory and medial brain regions (the mouse equivalent of the human default mode network) to subcortical targets involved in action and emotion. At the same time, it weakens cortico-cortical feedback loops — the recurrent neural circuits associated with rumination and repetitive negative thinking.

In plain language: psilocybin breaks the mental loops that keep you stuck in depressive thought patterns while simultaneously building stronger connections between perception, emotion, and action.

As Kwan explained: “Rumination is one of the main points for depression, where people have this unhealthy focus and they keep dwelling on the same negative thoughts. By reducing some of these feedback loops, our findings are consistent with the interpretation that psilocybin may rewire the brain to break, or at least weaken, that cycle.”

This study also confirmed something important: the rewiring is activity-dependent. That means the new connections aren’t random — they’re shaped by the neural activity that occurs during the psilocybin experience itself. The trip matters. The thoughts, emotions, and insights you have during your journey are literally sculpting your brain’s new architecture in real time.

How Psilocybin Triggers Neuroplasticity: The Molecular Pathway

So how does a single molecule trigger all of this structural change? Let’s trace the pathway.

Step 1: Psilocin Activates Serotonin 2A Receptors

When you consume magic mushrooms, your body converts psilocybin into psilocin. Psilocin binds to serotonin 2A receptors (5-HT2A), which are densely concentrated on the apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons in the prefrontal cortex — the exact cells where spine growth occurs. A 2025 study published in Nature by Kwan’s team confirmed that psilocybin’s lasting structural effects specifically require 5-HT2A receptors and particular pyramidal cell types.

Step 2: BDNF and mTOR Pathways Are Activated

When those receptors are stimulated, they trigger a cascade of intracellular signaling pathways. The two most important are:

BDNF (Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor): Often called “fertilizer for the brain,” BDNF is a protein that promotes the survival, growth, and differentiation of neurons. Psilocybin has been shown to increase BDNF expression. A 2023 study published in Nature Neuroscience found that psychedelics promote plasticity by directly binding to the BDNF receptor TrkB — suggesting a mechanism independent of, or complementary to, 5-HT2A activation.

mTOR (mammalian Target of Rapamycin): This signaling pathway regulates cell growth and protein synthesis. When activated, it promotes the formation of new dendritic spines and synaptic connections. Psilocybin activates mTOR in the prefrontal cortex, directly driving spine growth.

Step 3: New Spines Form and Mature

Within hours of psilocybin administration, new dendritic spines begin to appear. These nascent spines take about 4 days to mature into functional synapses. The Yale study showed that a fraction of these psilocybin-induced spines remained stable for at least a month, suggesting they’ve been fully integrated into the brain’s circuitry.

Step 4: Excitatory Neurotransmission Increases

The new spines aren’t just structural — they’re functional. The Yale team measured increases in miniature excitatory postsynaptic currents (mEPSCs), confirming that the newly grown connections are actively transmitting signals. The brain isn’t just growing new hardware; it’s turning it on.

What About Microdosing?

Most of the spine density research has been conducted with full psychedelic doses. But what about microdosing?

The honest answer: we don’t know for certain yet. There are far fewer studies on microdose-level neuroplasticity. But there’s reason to be optimistic.

A 2024 study published in the Journal of Psychopharmacology found that psilocybin promotes neuroplasticity and produces antidepressant-like effects in mice at varying doses. Preclinical evidence from the OPEN Foundation’s systematic review shows that neuroplastic effects — including elevated BDNF, spine density changes, and neurogenesis markers — appear in a dose-dependent manner, with even lower doses producing measurable effects in some studies.

There’s also the indirect evidence from the Stamets Protocol (psilocybin stacked with Lion’s Mane and Niacin), which Paul Stamets theorizes could amplify neuroplastic effects at sub-perceptual doses. Lion’s Mane independently stimulates Nerve Growth Factor (NGF), potentially complementing psilocybin’s effects on BDNF and spine growth. If you’re curious about microdose capsules that use these kinds of blends, check out our Microdose Capsules: Benefits, Blends, and What to Expect.

The bottom line: full doses have the strongest evidence for structural neuroplasticity. But microdosing likely contributes to neuroplastic change too — we just need more studies to confirm the dose-response relationship.

Psilocybin vs. Traditional Antidepressants: A Different Approach to the Same Problem

Traditional SSRIs (like Zoloft, Prozac, and Lexapro) increase serotonin availability in the brain. They can be effective for many people, but they come with significant limitations:

- They take 4–6 weeks to produce noticeable effects

- They must be taken daily, often for years or indefinitely

- They come with side effects like weight gain, sexual dysfunction, and emotional blunting

- They don’t appear to directly rebuild lost neural connections

- Stopping them can cause withdrawal symptoms

Psilocybin works through a fundamentally different mechanism. Rather than chronically modulating serotonin levels, it produces an acute burst of 5-HT2A activation that triggers a cascade of structural changes — new spines, new connections, new pathways — that persist long after the compound has left the body.

It’s the difference between taking a daily supplement to manage a deficiency versus doing a single intensive treatment that repairs the underlying damage.

That said, psilocybin isn’t a replacement for SSRIs for everyone. It’s not FDA-approved for depression (yet). It requires careful preparation, the right setting, and ideally professional guidance. And it’s not appropriate for people with certain conditions like schizophrenia or a family history of psychosis. But the neuroplasticity research makes a compelling case that psilocybin addresses depression at a deeper, structural level than most current treatments.

The Bigger Picture: Neuroplasticity Beyond Depression

While depression has been the primary focus of psilocybin neuroplasticity research, the implications extend far beyond mood disorders.

PTSD: Fear-based disorders involve rigid neural circuits that lock people into trauma responses. Research from Kwan’s lab has shown that psilocybin facilitates fear extinction in mice — the process of unlearning fear responses — through neuroplastic mechanisms. This has obvious implications for PTSD treatment.

Addiction: Substance use disorders are associated with reduced prefrontal cortex function and weakened executive control circuits. By rebuilding connections in these areas, psilocybin could help restore the brain’s ability to regulate impulses and make healthier decisions. Early clinical trials at Johns Hopkins have shown promising results for psilocybin-assisted therapy in treating alcohol and tobacco addiction.

Neurodegenerative Diseases: A groundbreaking pilot study from UCSF tested psilocybin on Parkinson’s disease patients and found improvements not just in mood, but in cognition and motor function. The researchers suggested psilocybin may help the brain repair itself by reducing neuroinflammation and promoting neuroplasticity — the same spine-growing mechanism documented at Yale.

Cognitive Flexibility: Even in healthy individuals, psilocybin’s neuroplastic effects may enhance creative thinking, problem-solving, and the ability to break out of rigid thought patterns. This is likely part of why microdosing has become so popular among creatives and professionals.

What This Means for You

If you’re reading this and thinking, “Okay, so psilocybin literally grows new brain connections. What do I do with that information?” — here are some practical takeaways:

1. The Trip Is Part of the Medicine

The 2025 Cell study confirmed that psilocybin’s rewiring is activity-dependent. The neural activity during your experience shapes which connections are built. This means set and setting aren’t just nice-to-haves — they’re biologically important. Go in with intention. Create a safe, comfortable environment. The quality of your experience directly influences the quality of your brain’s restructuring. Our 10 Best Activities on Magic Mushrooms blog can help you plan.

2. Integration Matters More Than You Think

New spines take about 4 days to mature into functional synapses. The weeks following a psilocybin experience are a critical window where your brain is consolidating new connections. This is why integration — journaling, therapy, reflection, and mindful lifestyle choices — is so important. You’re not just processing the experience emotionally; you’re supporting the biological maturation of new neural pathways.

3. Spacing Your Sessions Is Smart Biology

Your brain needs time to build and stabilize new connections. Rushing back for another trip before the previous round of neuroplasticity has matured is counterproductive. The standard recommendation of waiting at least 14 days between sessions isn’t just about tolerance — it’s about giving your brain time to finish its construction project. For more on this, read our full guide on Psilocybin Tolerance.

4. Support Your Brain’s Building Materials

Neuroplasticity requires raw materials: protein, omega-3 fatty acids, B vitamins, adequate sleep, and regular exercise. If you’re interested in maximizing the neuroplastic potential of psilocybin, support your brain with good nutrition, quality rest, and physical activity before and after your experience. Think of it like providing building materials for a construction crew that’s about to get to work.

5. Choose Your Strain Wisely

Different strains produce different intensities of experience, which likely correlates with different levels of receptor activation and neuroplastic stimulation. If you’re specifically interested in the therapeutic and neuroplastic potential, a moderate-to-strong experience with a well-characterized strain is likely more effective than a barely-perceptible microdose. Our guide on How Different Strains Affect Your Experience can help you choose.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does psilocybin actually grow new brain cells?

The Yale research focused on dendritic spines — new connections between existing neurons — rather than entirely new brain cells (neurogenesis). However, other studies have shown that psilocybin can promote neurogenesis in the hippocampus (the growth of brand new neurons), particularly at low to moderate doses. So the answer is: it does both — grows new connections and potentially new cells.

How long do the new connections last?

The Yale study tracked spines for 34 days and found that a significant portion of the new connections were still present. The 2025 Cell study confirmed that the network-level rewiring is also persistent. The exact upper limit isn’t known, but the structural changes appear to last at least several weeks to months.

Do I need a “heroic dose” for neuroplasticity?

Not necessarily. The Yale mouse study used a dose equivalent to a moderate human experience. The neuroplastic effects appear to be dose-dependent, meaning more intense experiences may produce more structural change. But even moderate doses produced significant spine growth. The key is having a meaningful experience, not an overwhelming one.

Can I see these changes on a brain scan?

A 2024 study published in Nature used precision functional mapping (fMRI) in humans and confirmed that a single dose of psilocybin produces detectable changes in brain connectivity that persist for weeks after the experience. So while we can’t see individual dendritic spines in living humans, we can see the larger-scale connectivity changes that result from them.

Is this why psilocybin helps with depression when SSRIs don’t?

Possibly. SSRIs work by increasing serotonin availability but don’t directly promote spine growth. Psilocybin activates the same receptor system but through a different mechanism — an acute burst of 5-HT2A activation that triggers structural remodeling. For people with treatment-resistant depression, this structural approach may address the root cause (lost connections) rather than just managing the symptoms.

The Bottom Line

The science is clear and getting clearer every year: psilocybin doesn’t just change how you feel during a trip. It physically changes the structure of your brain — growing new connections, strengthening communication between neurons, and selectively rewiring neural networks in ways that break the patterns underlying depression, anxiety, and rigid thinking.

From the landmark 2021 Yale study showing a 10% increase in dendritic spine density from a single dose, to the 2025 Cell paper mapping exactly how psilocybin rewires entire brain networks, the evidence paints a consistent picture: this compound promotes rapid, lasting structural change in the brain regions most affected by mental illness.

We’re still in the early chapters of understanding psilocybin’s full neuroplastic potential. But what we know so far is extraordinary — and it explains why so many people describe their mushroom experiences as genuinely life-changing.

Because at a biological level, they are.

Happy tripping!

Curious to explore the neuroplastic potential of psilocybin for yourself? Browse our full selection of magic mushrooms, or start with our microdose capsules for a gentler introduction.

Sources

- Shao et al. (2021) — “Psilocybin induces rapid and persistent growth of dendritic spines in frontal cortex in vivo” — Neuron — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34228959/

- Yale News (2021) — “Psychedelic spurs growth of neural connections lost in depression” — https://news.yale.edu/2021/07/05/psychedelic-spurs-growth-neural-connections-lost-depression

- Jiang et al. (2025) — “Psilocybin triggers an activity-dependent rewiring of large-scale cortical networks” — Cell — https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(25)01305-4

- Cornell Chronicle (2025) — “A dose of psilocybin, a dash of rabies point to treatment for depression” — https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2025/12/dose-psilocybin-dash-rabies-point-treatment-depression

- Shao et al. (2025) — “Psilocybin’s lasting action requires pyramidal cell types and 5-HT2A receptors” — Nature — https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40175553/

- OPEN Foundation (2025) — “Psilocybin and Neuroplasticity: A Review of Preclinical and Clinical Studies” — https://open-foundation.org/psilocybin-and-neuroplasticity/

- Siegel et al. (2024) — “Psilocybin desynchronizes the human brain” — Nature — https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-024-07624-5

- UCSF (2025) — “How Magic Mushrooms Could Help Parkinson’s Disease Patients” — https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2025/04/429906/how-magic-mushrooms-could-help-parkinsons-disease-patients

- Health Canada — Psilocybin and Psilocin (Magic Mushrooms) — https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/substance-use/controlled-illegal-drugs/magic-mushrooms.html

- Johns Hopkins Center for Psychedelic & Consciousness Research — https://www.hopkinspsychedelic.org/

Disclaimer: This blog is for educational and harm reduction purposes only and is not medical advice.